During the recent Covid-19 restrictions, as citizens have had to face challenges that have greatly affected daily life, Barbara Ursini Novelli thought it timely to look more closely at the theme of isolation. Delving into the oral archives at the New Zealand Maritime Museum, she discovered interviews with three women who lived in lighthouses in different decades spanning the early years of the 20 century until 1971. The interviewees described their lives and what it was like living in ongoing isolation without modern conveniences and limited access to medical services. Some of their experiences encourage us to review our current circumstances and reflect on the changes that have occurred in over a century.

By Barbara Ursini | 2021

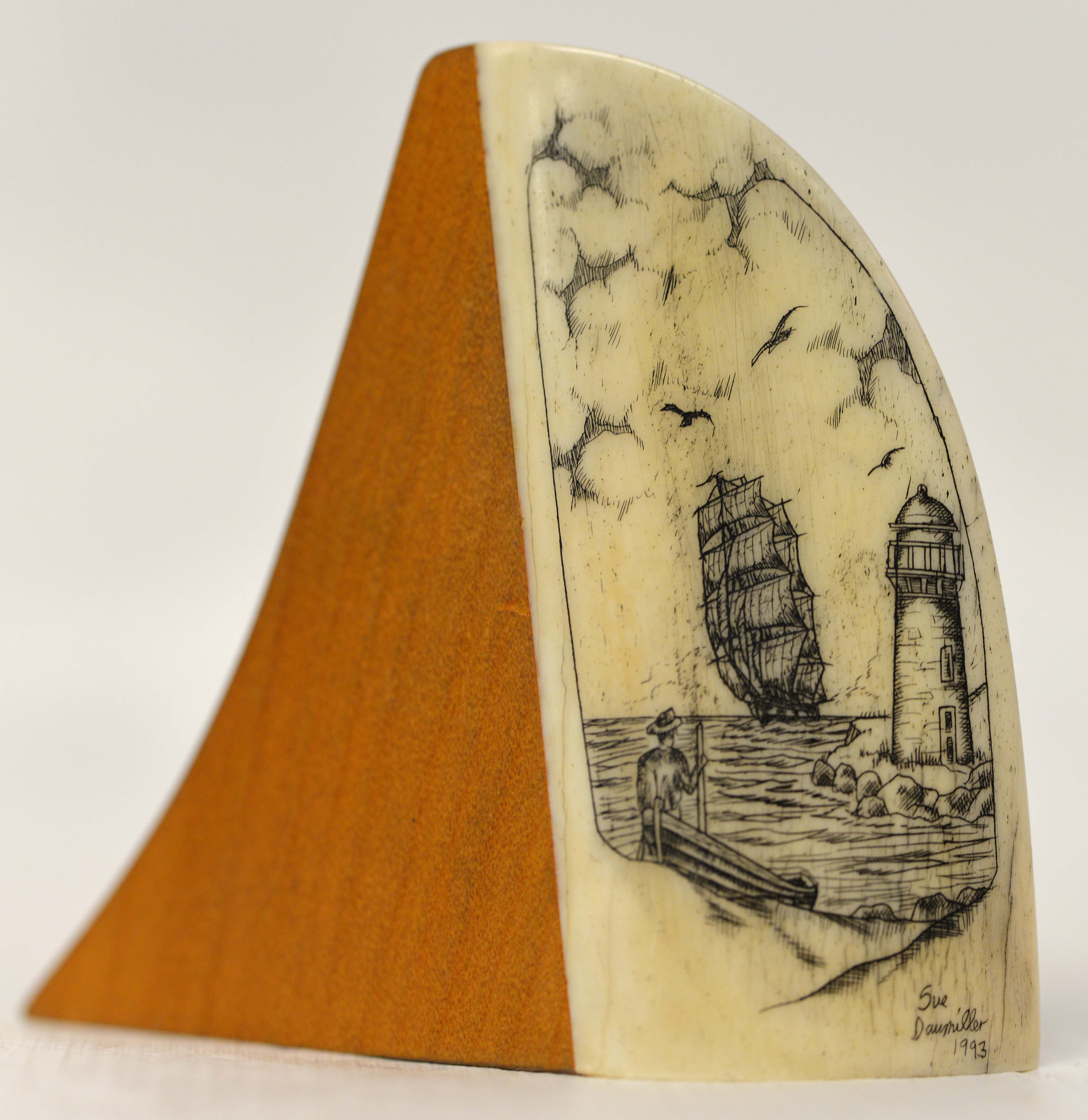

Artist Sue Daumiller created this scrimshaw image in 1993. It depicts a scene from bygone years, showing a solitary man, possibly a lighthouse keeper, looking on as a ship approaches a nearby lighthouse.

New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui A Tangaroa (1999.40.3)

Elsie Eagle

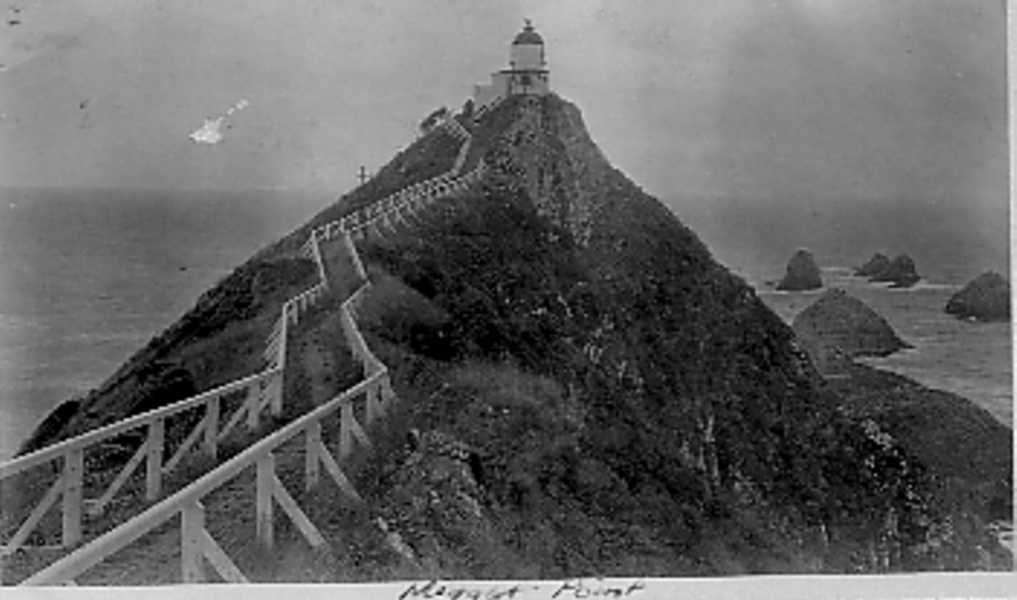

Elsie Eagle was the daughter of a lighthouse keeper. Born in 1906, she remembers living at three different stations: Portland Island, located off Māhia Peninsula, Cape Saunders at Muaupoko, on the Otago Peninsula, and also Nugget Point in the Catlins, where her family were based from 1914-1922. Elsie’s first school was at “the Nuggets” and the principal keeper’s daughter was the teacher. There were only three other families on the island. To supplement the provisions that were delivered by boat, families would grow their own produce. Elsie recalls that “Dad would go fishing and hunt rabbits”. She remembers watching and assisting her father on the night shift; each keeper had a six-hour shift and communications were sent using morse code.

Nugget Point lighthouse was closer to a town than many other lighthouses.

Gift of Wellington Museums Trust, New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui A Tangaroa (2012.0.122)

Rosalind Hosking

In 1948, Rosalind Hosking was three months pregnant when she and her husband, a lighthouse keeper, first went to live on Stephens Island. She describes the house as being “ancient and cold”. Their first year was without electricity, so they needed to order kerosene for lamps. Although supplies were delivered regularly, the Marine Department advised to the family to keep six weeks supply on hand. Initially, without power, it was a challenge to store meat, so a sheep was killed each fortnight and shared between the other families. There were no washing machines and Rosalind notes that after this experience, she started to appreciate small things such as water on tap. The family spent four years on Stephens Island with three children.

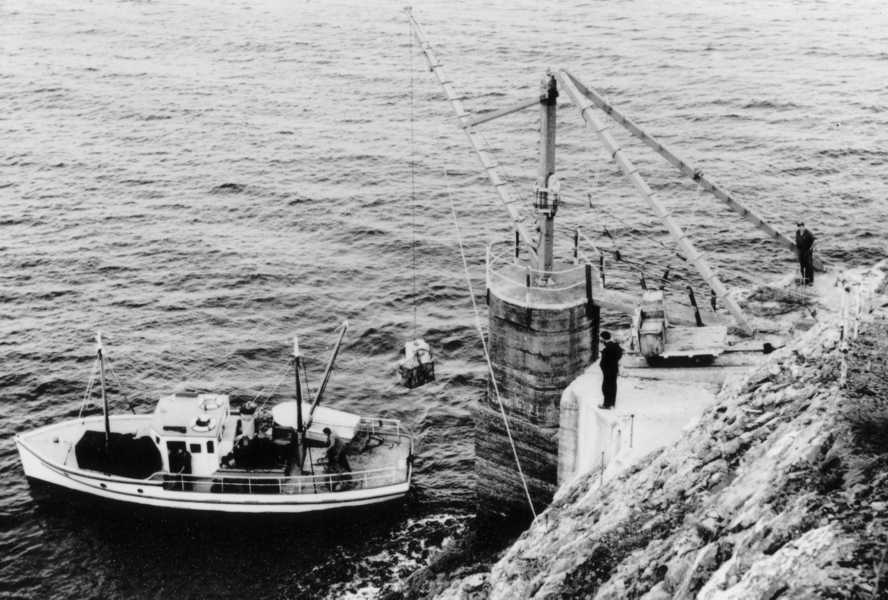

At Stephens Island, passengers and supplies were winched ashore in a basket. It was a steep climb up the path to the exposed lighthouse, situated 183 metres above sea level, at the top of the South Island and overlooking the Cook Strait.

Gift of Wellington Museums Trust, New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui A Tangaroa (2012.0.3661)

Carol McGregor

Carol McGregor and her husband moved to Cuvier Island in 1969 and lived there until 1971. It was not a pleasant experience for her and she felt extremely isolated. When her husband broke his arm and had to get medical attention, Carol was left to look after her three children and help in the lighthouse for 10 days. Conditions improved somewhat when the family was transferred to Stephens Island eight months later. While Carol took care of the correspondence and housework, her husband looked after the upkeep outside the house. She recalls that getting on and off the island by boat was difficult; one had "to be like Tarzan".

Carol found dealing with both the Marine Department and principal keeper challenging. At one stage, when she suffered a miscarriage, it took some hours before a helicopter was dispatched to take her to hospital. Visitors to the island were so scarce that when a helicopter arrived one time, carrying the Governor General, she recalls that “the kids thought they were Martians”.

So, even with the introduction of electricity and improved technologies such as radio communication, prolonged isolation sometimes proved challenging. Frequently removed from access to ready services, women need to be resilient, self-reliant and self-sufficient. If the men were sick or away, they had to take on extra duties and without pay. This type of lifestyle ended as automation saw the removal of keepers and families from service. Stephens Island and Nugget Point lighthouses were some of the last to be automated in 1989.

Ventris Williscroft, pictured here with her Siamese cat, and her lighthouse keeper husband Murray worked on a number of stations around New Zealand in the 1950s-60s.

Gift of Rae MacGregor, reproduced courtesy of Ventris Williscroft, New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui A Tangaroa (2015.152.6)

Primary source of information:

Recordings made at a lighthouse keepers’ reunion, Lower Hutt, 1990. New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui A Tangaroa (1990.217)

The Bill Laxon Maritime Library, located at the New Zealand Maritime Museum, has a number of books about living and working at New Zealand lighthouses, including the biographies of lighthouse families:

-

As darker grows the night by Peter Taylor, 1975

-

The lighthouse keeper’s wife: an autobiography by Jeanette Aplin,2001

-

The children from the lighthouse by Mabel Pollock, 2007

-

The tall white tower by W. E. H. Creamer, Terence Cole, 2013

Written by Bárbara Ursini Novelli