Having a Boogie with Strangers in Town

We pay tribute to a group of women who, from the 1940s until 1981, put on weekly dances for seafarers visiting the port of Auckland. The following story of the big-hearted hostesses who could do the polka, the elephant walk, and the hasapiko appears in Endless Sea: Stories told through the taonga of the New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui te Ananui a Tangaroa.

By Frances Walsh | 13 Nov 2020

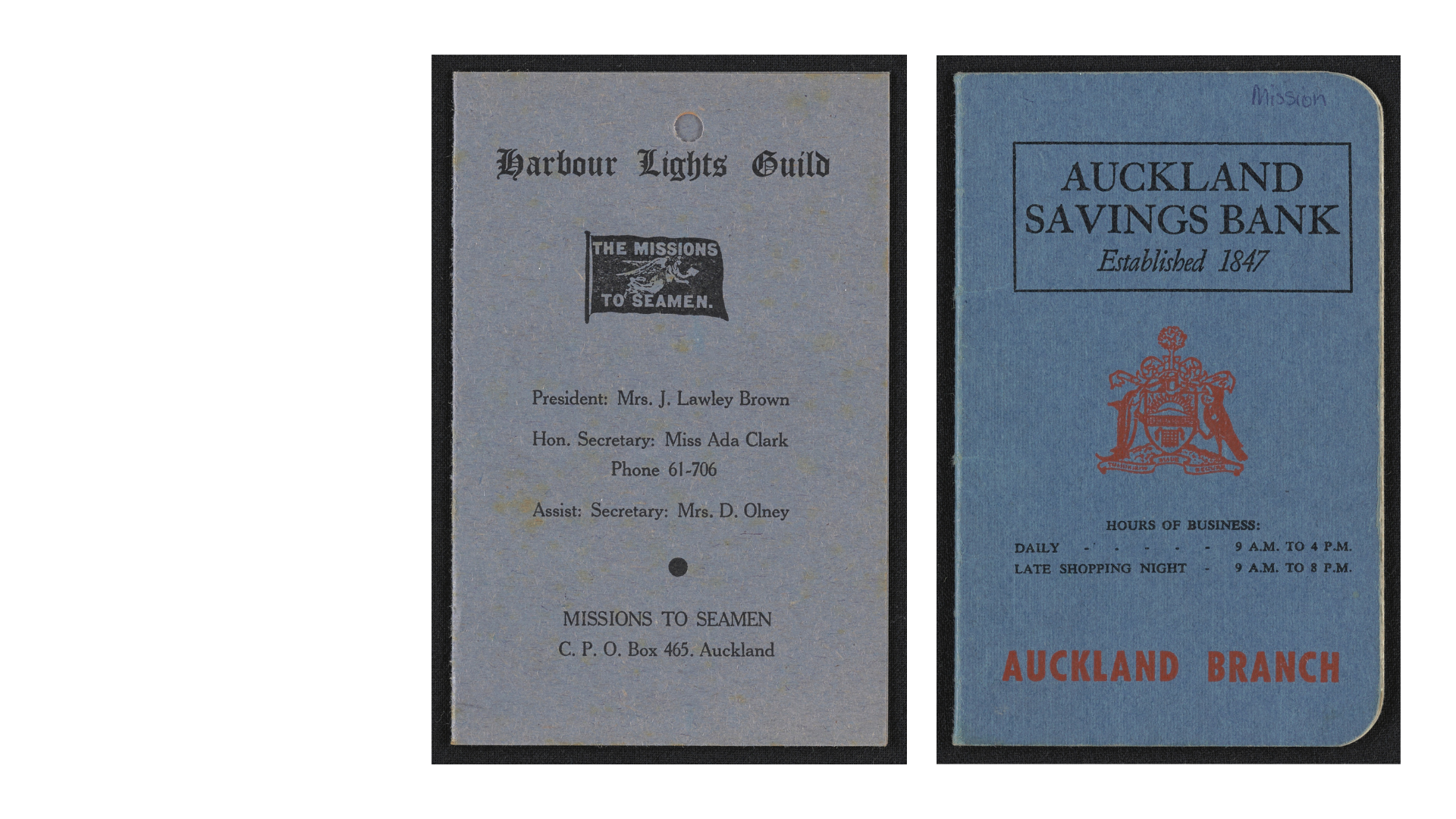

For much of the last century seafarers who wanted to share the company of an Anglican woman while in the port of Auckland could go along to the Mission to Seamen, popularly known as the Flying Angel. From 1919 to 1980 the welfare organisation was greatly assisted by female volunteers, who belonged to either the Harbour Lights Guild or its junior arm, the Younger Set. The women fundraised with jumble sales and fairs, and dispatched books to lighthouse keepers and their families; they sent seamen Christmas and sympathy cards, gave them home-cooked meals, took them on outings, and visited them in hospital or in jail.

It was also the role of those in the Younger Set to act as hostesses at the mission’s weekly Tuesday night dances which began at 8 p.m., and could be lively. The annual reports of the Younger Set record that in 1950-51 music was provided by a live trio; in 1975-76 a cadet from MV Otaio performed an Irish jig, Polish sailors demonstrated the polka, and French, Greek, and Yugoslav officers invited hostesses to learn their respective traditional moves; and in 1976-77, when average attendances at the dances had dwindled to 13, three stewards from the liner SS Oriana helped with the supper dishes before teaching hostesses the elephant walk, a dance inspired by the 1961 Henry Mancini instrumental.

At least in the 1970s, when young women joined the Younger Set they were given a set of instructions, ‘commonsense rules’, issued by the mission’s general secretary in the London HQ. First up, a hostess ‘treads a narrow line between friendly interest in the individual and the possibility that friendliness might be understood as an invitation to something else’. Therefore, don’t invite a seafarer home, if you live alone. Don’t visit a ship, unless in a group.

‘The main thing to remember is that seafarers are ordinary blokes, but the kind of life they lead means that they want to pack a lot of living into the periods they spend ashore. We’re not suggesting that birds and booze are their main aims in life, far from it, but it’s as well to be aware of situations that may arise.’

It was also suggested that hostesses attend church services at the mission, and invite seamen to do likewise, ‘though it is unwise to press the point if the man seems reluctant’. More prosaically, the instruction sheet laid out duties: at suppertime (8.45-9 p.m.) ferry tea and sandwiches to each table; chat to seamen if possible: ‘Because of language difficulties you may not always be able to converse with some seamen but your presence at their table will be sufficient proof that they are our accepted guests.’ And, clear the tables before recommencing dancing.

It certainly wasn’t a free-for-all at the mission. On 26 April 1966 it was minuted in a Younger Set’s committee meeting that ‘the Non-Smoking rule of the Club was not being observed, and notices were to be displayed requesting girls to refrain from smoking in the Dance Hall and the Canteen. Also, it was decided that slacks were not to be worn at the Mission and a notice to this effect was to be displayed.’ By 1971, however, conservative forces were receiving push-back—minutes taken at a 6 April meeting that year stated: ‘Dress: The Padre expressed his disapproval of trouser suits at dances or canteen, but the girls were agreed that one should regard dress as secondary and the girls’ attitude and friendship towards the men, their manner and interest etc. was the prime factor.’

Despite the hostesses’ big hearts, by the 1970s the dances weren’t proving popular. The mission struggled to find interested unmarried women.

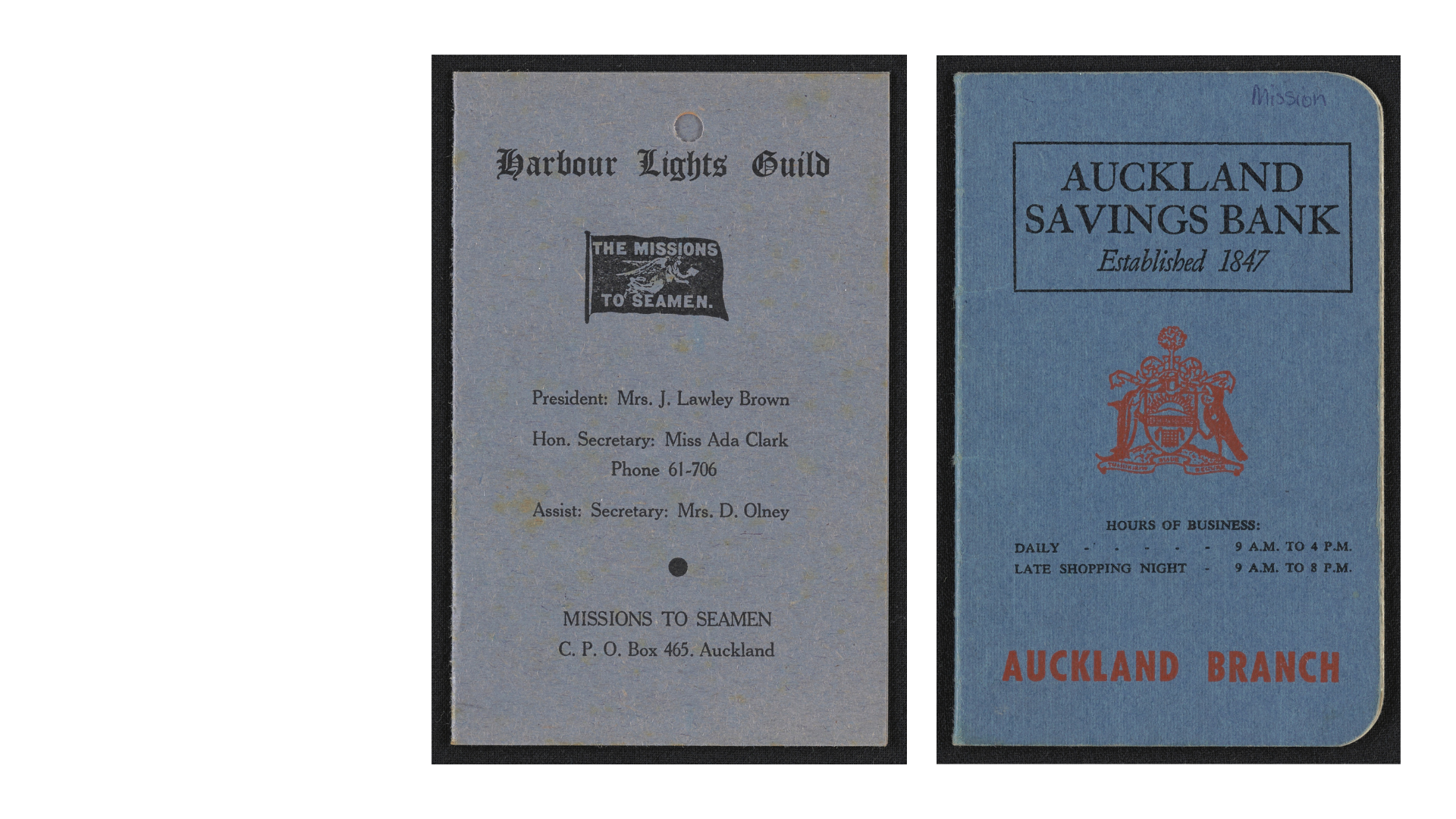

From minutes in 1971: ‘The Padre should put a request for more girls regularly in the Newsletter, and possibly also write to all vicars to send some girls from each parish. It was asked if married and separated women could attend the dance and Padre agreed this ruling should be broadened.’ There was a not-unrelated issue: the blokes were no shows—as container ships with their quick turnarounds began to dominate, sailors had less opportunity to cut the rug while in port. There was an attempt to shake up proceedings in the late 1970s, by inviting non-seagoing visitors to the dances, a development that prompted a letter to the Younger Set expressing concern that since the landlubbers appeared to be competent ballroom dancers, they were ‘an inhibiting effect on non-dancing seamen’. The Younger Set wound up in 1981, its little Auckland Savings Book shown here having a closing balance of $51.76, which was given to the mission.

Image credit (left) Harbour Lights Guild membership card, 1953. Collection of the Anglican Diocese of Auckland. New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui te Ananui a Tangaroa, L2020.2.1.

Image credit (right) Younger Set Harbour Lights Guild’s Auckland Savings Bank passbook, 1977-1981. Collection of the Anglican Diocese of Auckland. New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui te Ananui a Tangaroa, L2020.2.2.

With thanks to Jackie Marinkovich (Anglican Diocese of Auckland Archive), and Captain Chris Barradale, (Auckland Mission to Seafarers).

From: Endless Sea, Stories told through the taonga of the New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui te Ananui a Tangaroa. Written by Frances Walsh. Photographed by Jane Ussher. Massey University Press, $70.00.

If you have stories about the dances or the hostesses we’d love to hear them. Contact: frances.walsh@maritimemuseum.co.nz