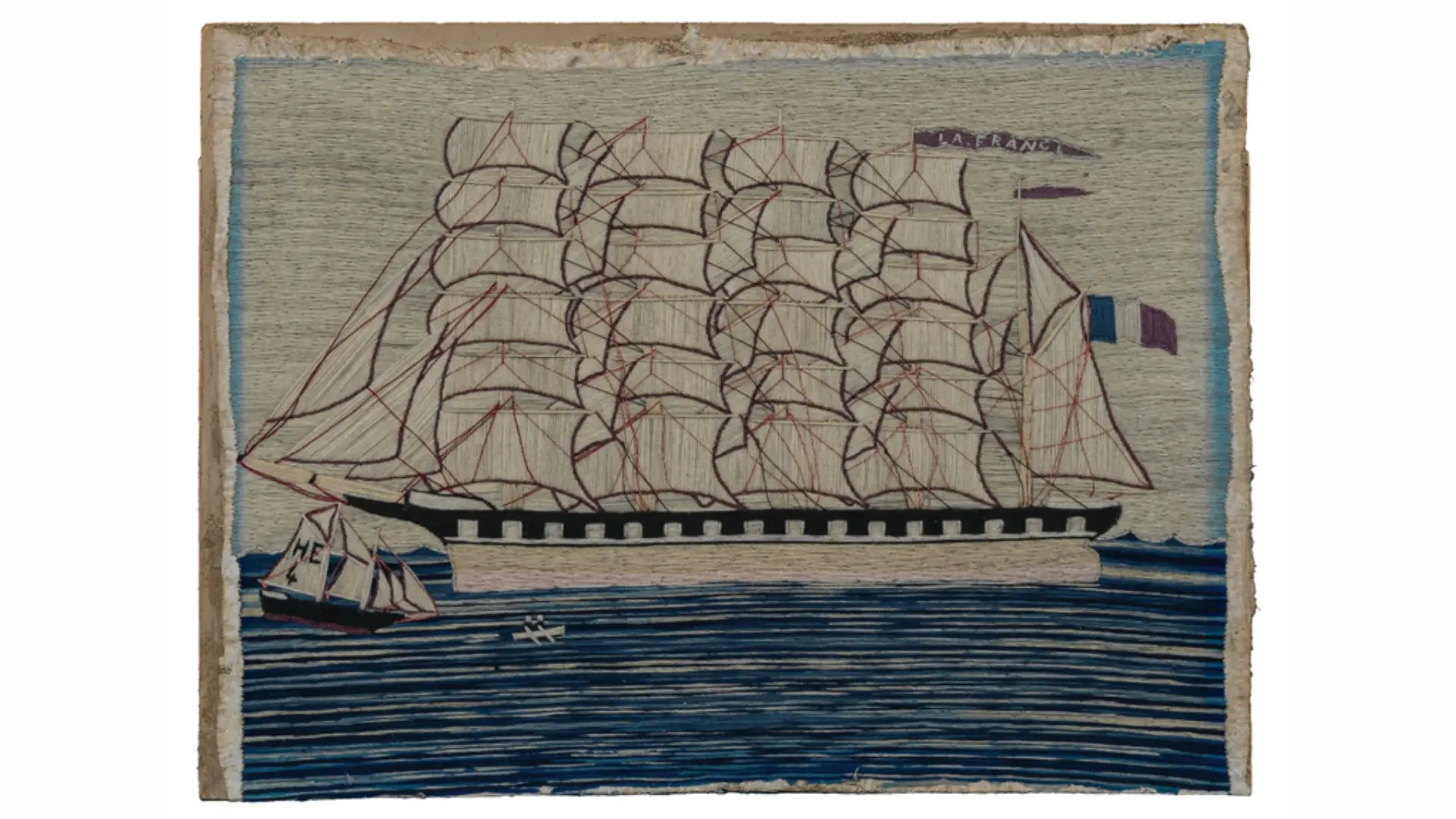

Like scrimshaw and fancy knotwork, embroidered ship portraits AKA woolies were the handiwork of men whose ships were propelled by the wind. They are a little-known and little-documented genre: undated and unsigned; stitched in wool—hence the nickname; and depict vessels broadside in full sail, allowing details and line to be accentuated and admired.

By Frances Walsh | 7 Feb 2023

Woolies were for the most part made by British sailors, from the mid-nineteenth century to the early twentieth. Production peaked between 1860 and 1880. One theory goes that they were inspired by Chinese embroideries, which sailors bought in Hong Kong and the Treaty Ports when they opened to the West in 1842.

The works reflect the Victorian vogue for things needlework. Seafarers had a jump start, routinely having to repair sails, as well as their own clothes and kit. Although it’s sometimes speculated that woolies were made at sea, in downtimes, it seems more likely that they were made on shore leave, or in retirement, when their makers were possibly feeling elegiac, wishing to conjure wide-open horizons. Stitch artist and London Royal School of Needlework graduate Jo Dixey has examined the museum’s reasonably large woolies shown here. The tension is mostly consistent, indicating that canvases were stretched taut on a frame before embroidering commenced—the activity would have required space, which seafarers in the nineteenth century didn’t usually have in their cramped quarters.

Duck linen was often used for the base of the woolie, and marked up with a schematic design in charcoal or pencil. Although there are examples of cotton and silk being used, Berlin wool was usually the thread of choice. The soft wool came from Saxony merinos, and after local combing and spinning, it was sent to Berlin for dyeing. It had advantages over English and Dutch wools in that it separated easily into strands, and quickly absorbed the new aniline or synthetic dyes that were developed from the mid-1850s and came in vibrant purples never seen before.

Woolie makers used a variety of stitches and techniques, such as cross and chain stitch, darning and trapunto (sometimes called the ‘stuffed’ quilting method, whereby an underlayer is padded to produce a raised surface). It was the long stitch, however, that dominated, being economical with wool and making for speedy sewing. The sea and sky were often worked horizontally in long stitch, and the sails vertically, lifting them from the background in relief. Rigging was rendered in linen, and cotton thread was tethered over the sails.