Samuel Clemens embarked on a sold-out lecture tour of New Zealand in 1895, well after he had invented the characters of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. The American humourist and writer—better known by his nom de plume Mark Twain—was impressed by the country’s natural splendours, but not by the Union Steam Ship Company AKA the Southern Octopus which was headquartered from 1875 in Ōtepoti Dunedin.

By Frances Walsh | 20 Jan 2023

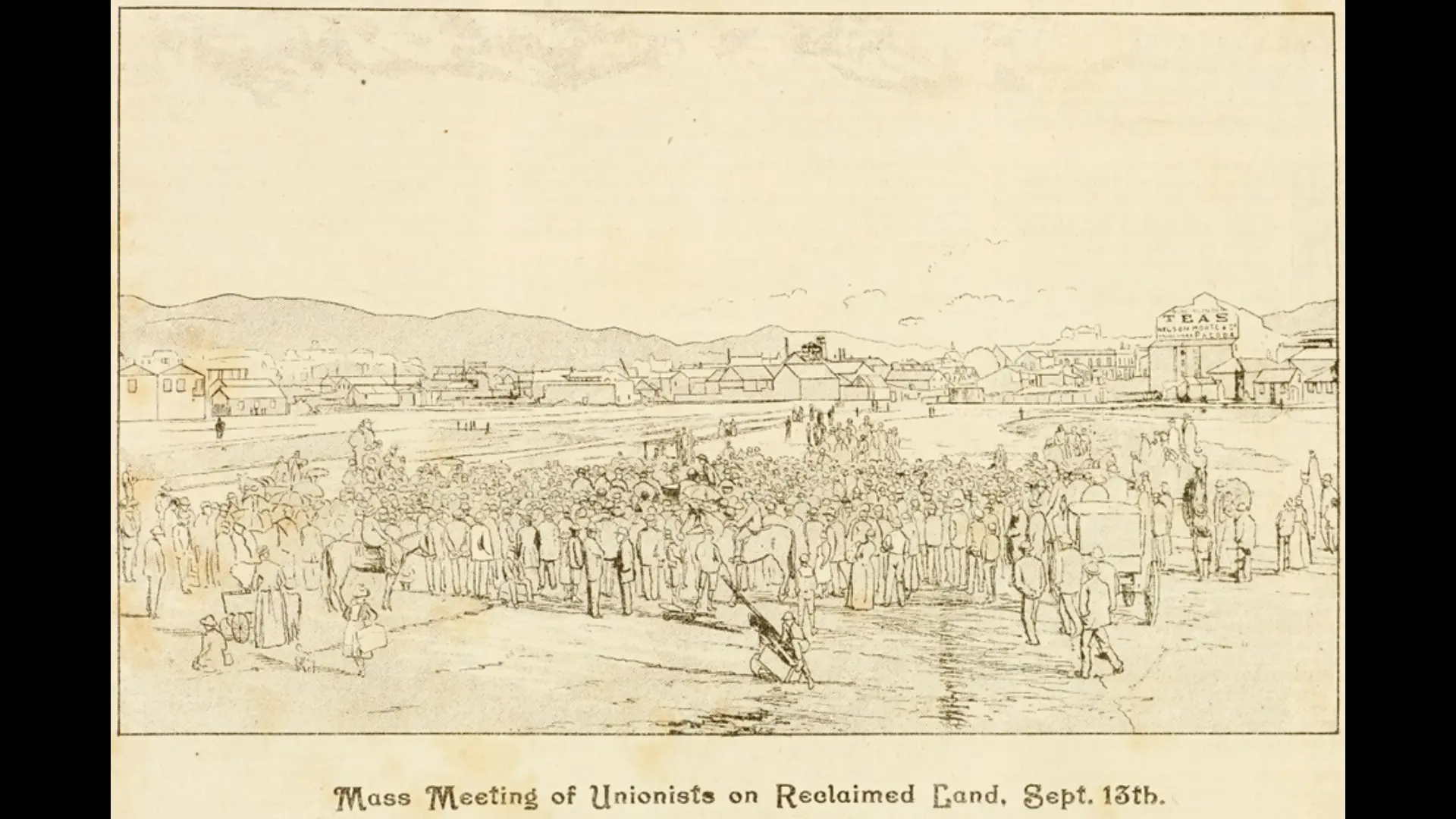

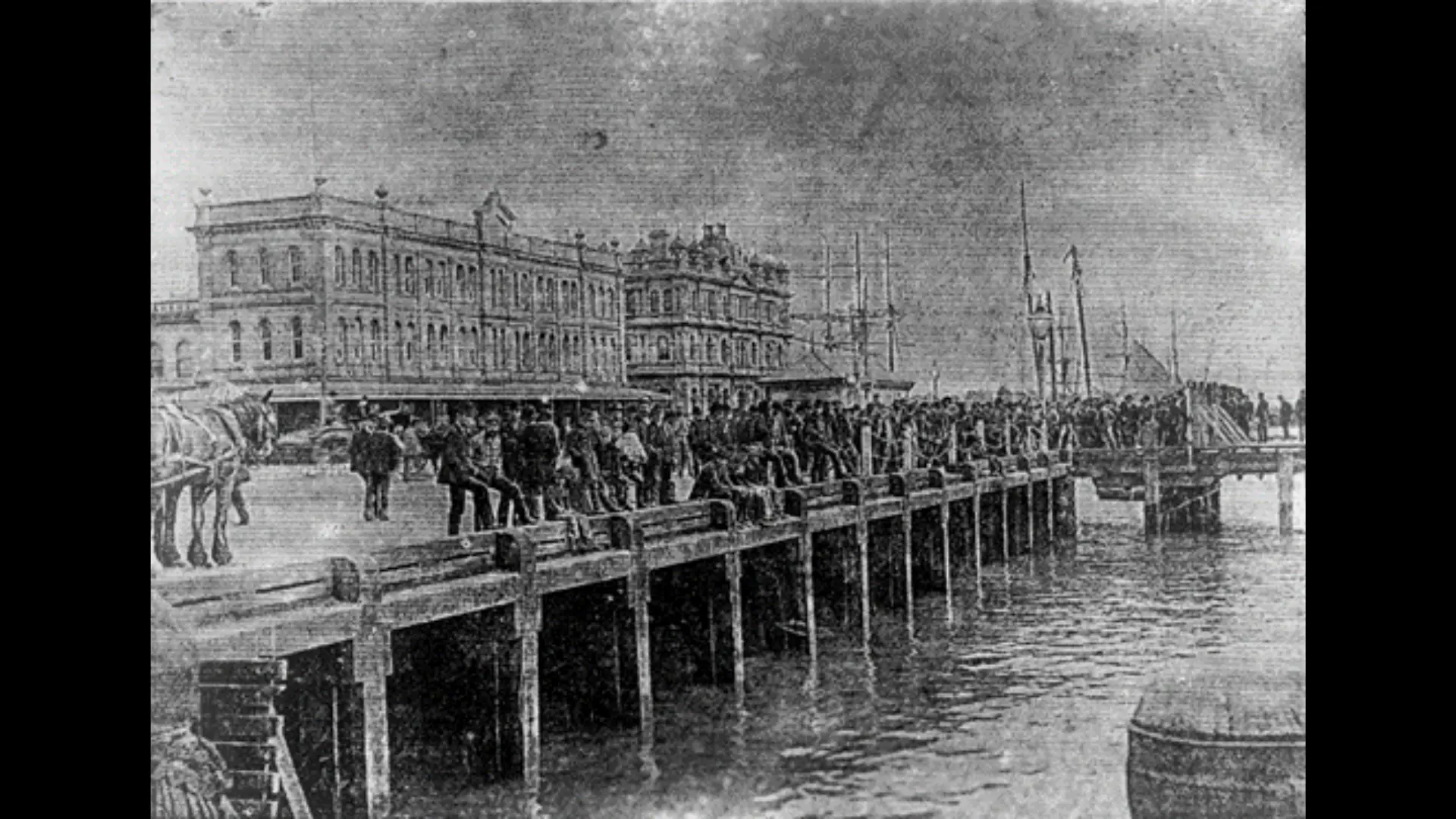

In 1895 Samuel Clemens was broke. To pay off his creditors he undertook a lecture tour of the British Empire, spending five weeks in Aotearoa over the months of November and December performing as his alias Mark Twain, assuming the characters of Huck and Tom and others, weaving into his ‘morals lecture’ his views on the human condition, Victorian hypocrisy, white privilege, and more. The Hawke’s Bay Herald called him ‘a heaven-sent genius’. Subsequently the celebrity published the travelogue Following the Equator, which included an attack on the Union Steam Ship Company (USSCo), nicknamed ‘the Southern Octopus’ for its market domination and known for its persecution of trade unionists during and after the 1890 maritime strike. Here’s Twain in Following the Equator remembering a voyage in November 1895, on the 1283-ton Flora, a steamship in the fleet of the USSCo:

‘Sunday, 17th. Sailed last night in the Flora, from Lyttelton. So we did. I remember it yet. The people who sailed in the Flora that night may forget some other things if they live a good while, but they will not live long enough to forget that.

The Flora is about the equivalent of a cattle-scow; but when the Union Company find it inconvenient to keep a contract and lucrative to break it, they smuggle her into passenger service, and “keep the change”. They give no notice of their projected depredation; you innocently buy tickets for the advertised passenger boat, and when you get down to Lyttelton at midnight, you find that they have substituted the scow. They have plenty of good boats, but no competition—and that is the trouble. It is too late now to make other arrangements if you have engagements ahead.

It is a powerful company, it has a monopoly, and everybody is afraid of it—including the government’s representative, who stands at the end of the stage-plank to tally the passengers and see that no boat receives a greater number than the law allows her to carry. This conveniently-blind representative saw the scow receive a number which was far in excess of its privilege, and winked a politic wink and said nothing. The passengers bore with meekness the cheat which had been put upon them, and made no complaint. It was like being at home in America, where abused passengers act in just the same way. A few days before, the Union Company had discharged a captain for getting a boat into danger, and had advertised this act as evidence of its vigilance in looking after the safety of the passengers . . . but when opportunity offered to send this dangerously overcrowded tub to sea and save a little trouble and a tidy penny by it, it forgot to worry about the passenger’s safety.

The first officer told me that the Flora was privileged to carry 125 passengers. She must have had all of 200 on board. All the cabins were full, all the cattle-stalls in the main stable were full, the spaces at the heads of companionways were full, every inch of floor and table in the swill-room was packed with sleeping men and remained so until the place was required for breakfast, all the chairs and benches on the hurricane deck were occupied, and still there were people who had to walk about all night! If the Flora had gone down that night, half of the people on board would have been wholly without means of escape. The owners of that boat were not technically guilty of conspiracy to commit murder, but they were morally guilty of it.

I had a cattle-stall in the main stable—a cavern fitted up with a long double file of two-storied bunks, the files separated by a calico partition—twenty men and boys on one side of it, twenty women and girls on the other. The place was as dark as the soul of the Union Company, and smelt like a kennel. When the vessel got out into the heavy seas and began to pitch and wallow, the cavern prisoners became immediately seasick, and then the peculiar results that ensued laid all my previous experiences of the kind well away in the shade. And the wails, the groans, the cries, the shrieks, the strange ejaculations—it was wonderful. The women and children and some of the men and boys spent the night in that place, for they were too ill to leave it; but the rest of us got up, by and by, and finished the night on the hurricane-deck.

That boat was the foulest I was ever in; and the smell of the breakfast saloon when we threaded our way among the layers of steaming passengers stretched upon its floor and its tables was incomparable for efficiency.’