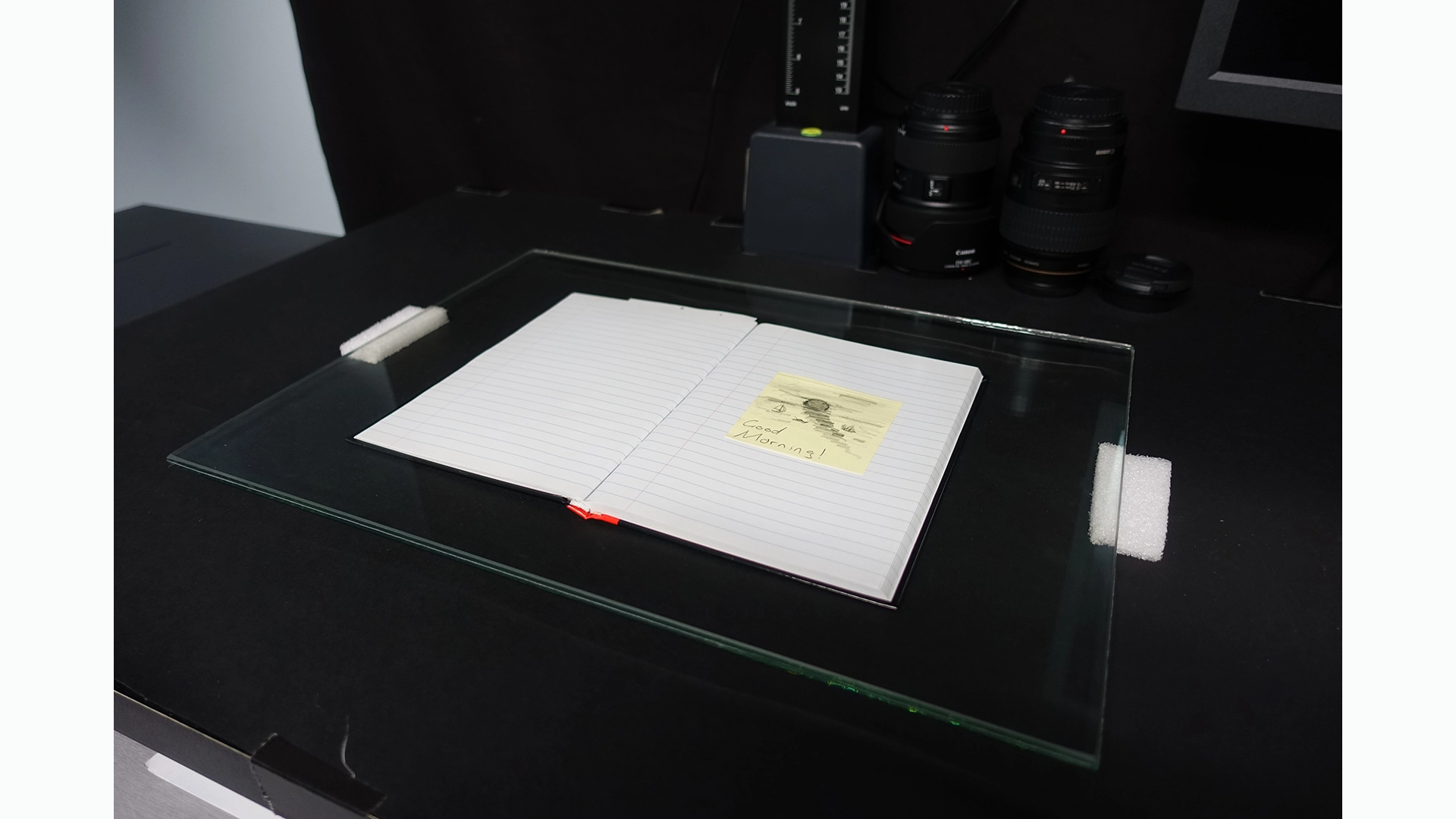

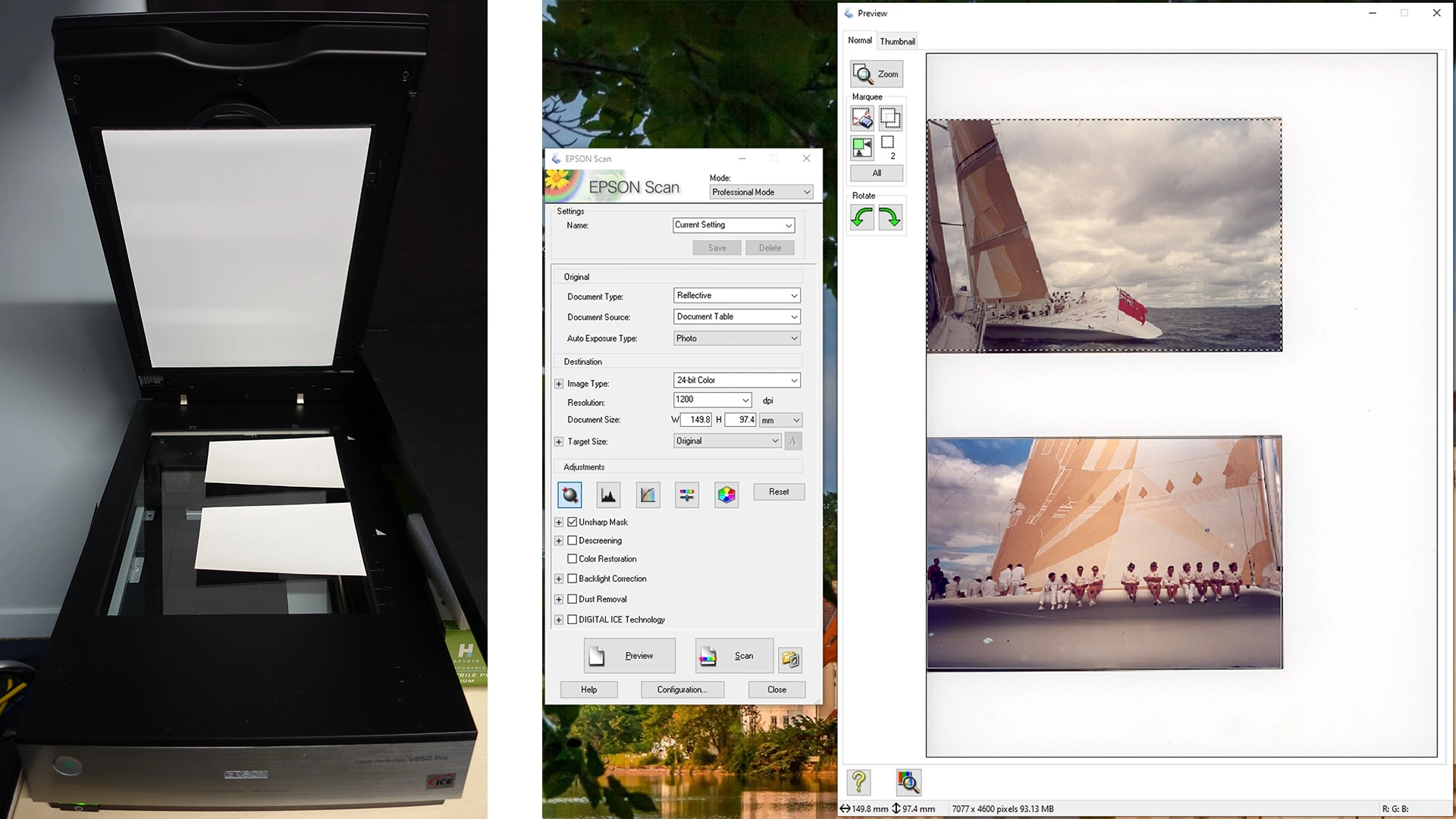

With the knowledge that lockdown was going to continue for longer than a few weeks in 2021, digitisation from home had to be organised so that we could continue to make progress, albeit at a slower pace. With special permission, a complete set of Bearings magazine, the New Zealand Maritime Museum publication, and an Epson V800 scanner were packed up and safely transported to the home office (that is a picnic table temporarily set up in the corner of the lounge and draped with Tyvek).

All 17 copies of Bearings were then digitised from home on the Epson scanner. It took between five and six hours to scan one copy of Bearings from front page to back page. Most issues contain around 60 pages, although there are one or two of around 80 pages. For greater context, if we had photographed Bearings in the office on our copy stand setup, it would have taken roughly twenty minutes per issue – a day’s work to do all 17. Instead, it took most of the lockdown to scan the set, scanning one magazine across two days in most cases. The complete set of Bearings is now available to be viewed on our NZMM Collections Online and PDF copies are available upon request.

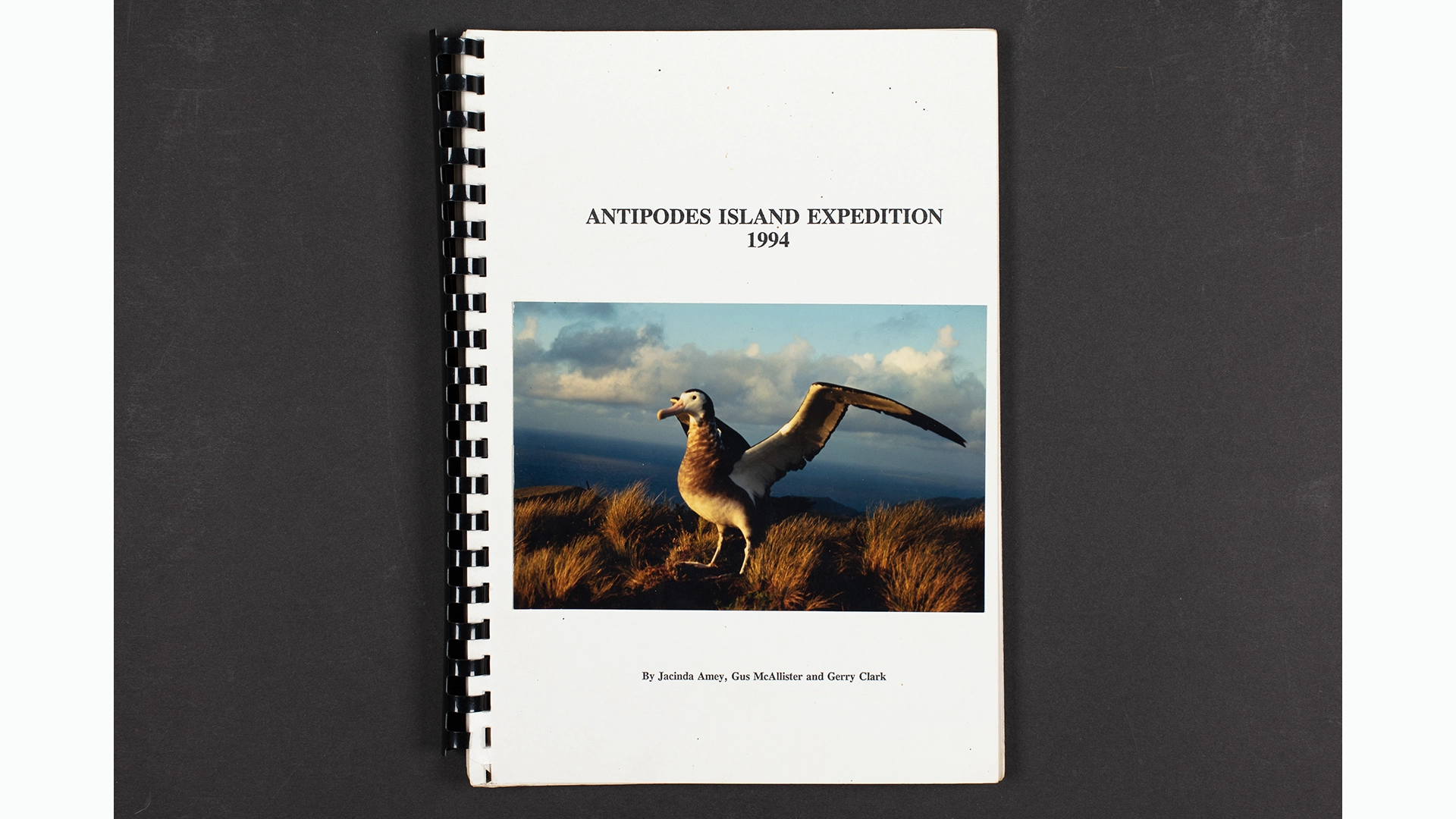

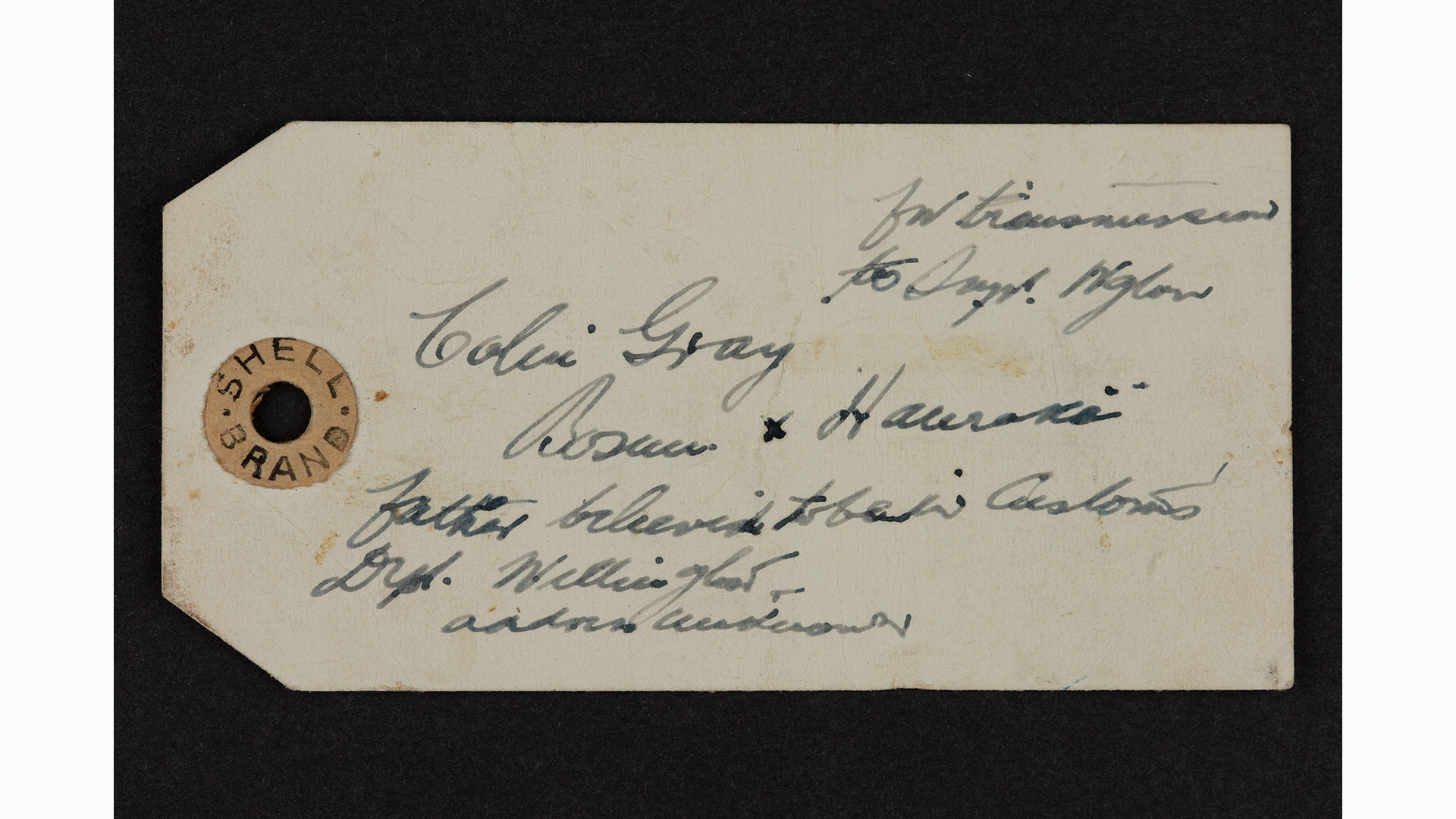

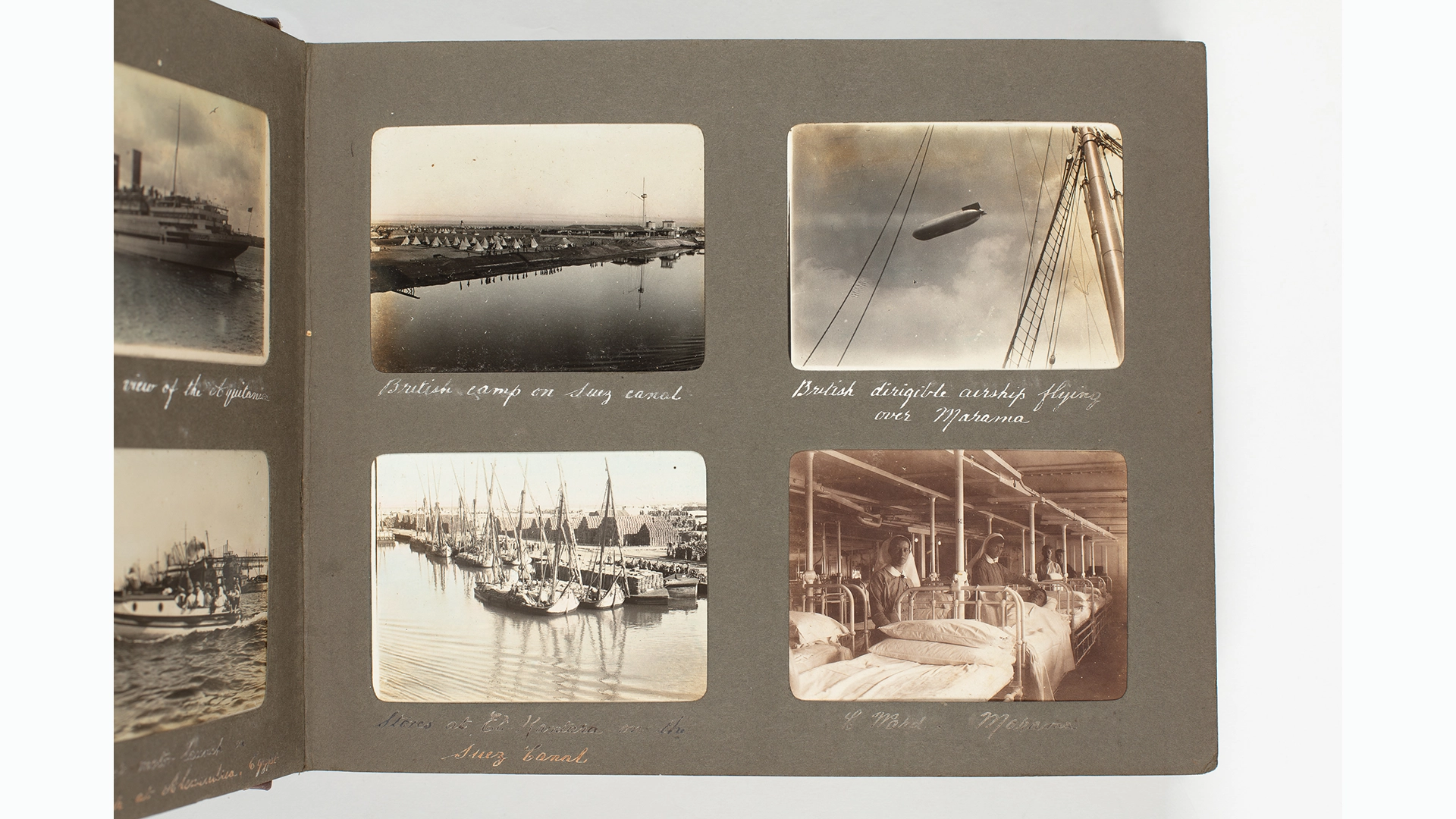

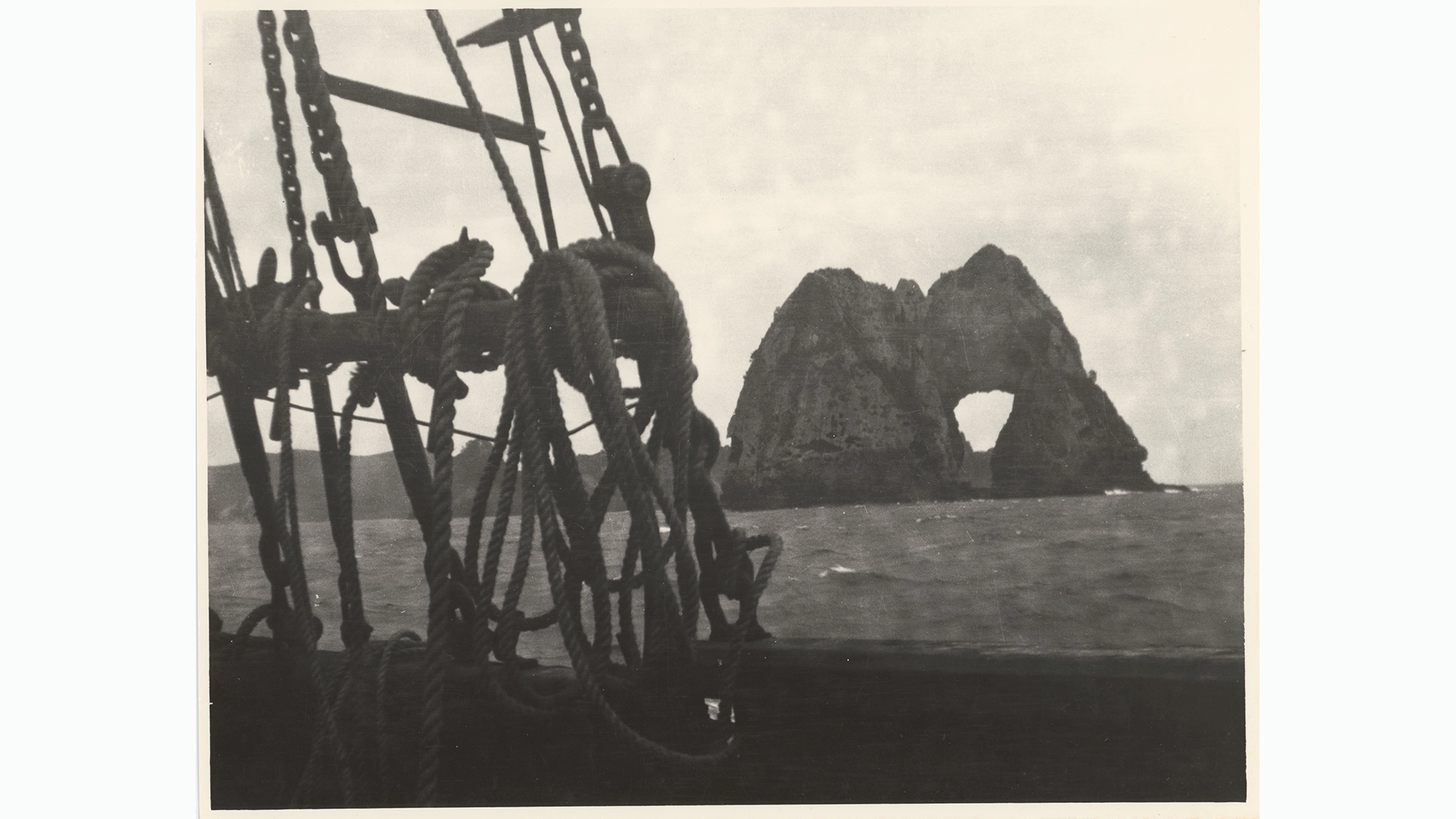

A collection of photographs was also scanned and catalogued from the home office to help introduce variety to the workstream.

As with any non-ideal circumstance, continuing to digitise from home, although necessary, came with its own complications. Not only was the output speed slower, but there were also problems with connectivity, lack of digital storage space, pandemic distractions and cats. At one point, when storage space was an issue, there were a few weeks where digitisation could not continue from home while we waited for our new hard drives and external storage to be shipped. We were up and running again thereafter!

Post-Processing and Technical Specifications for File Exports

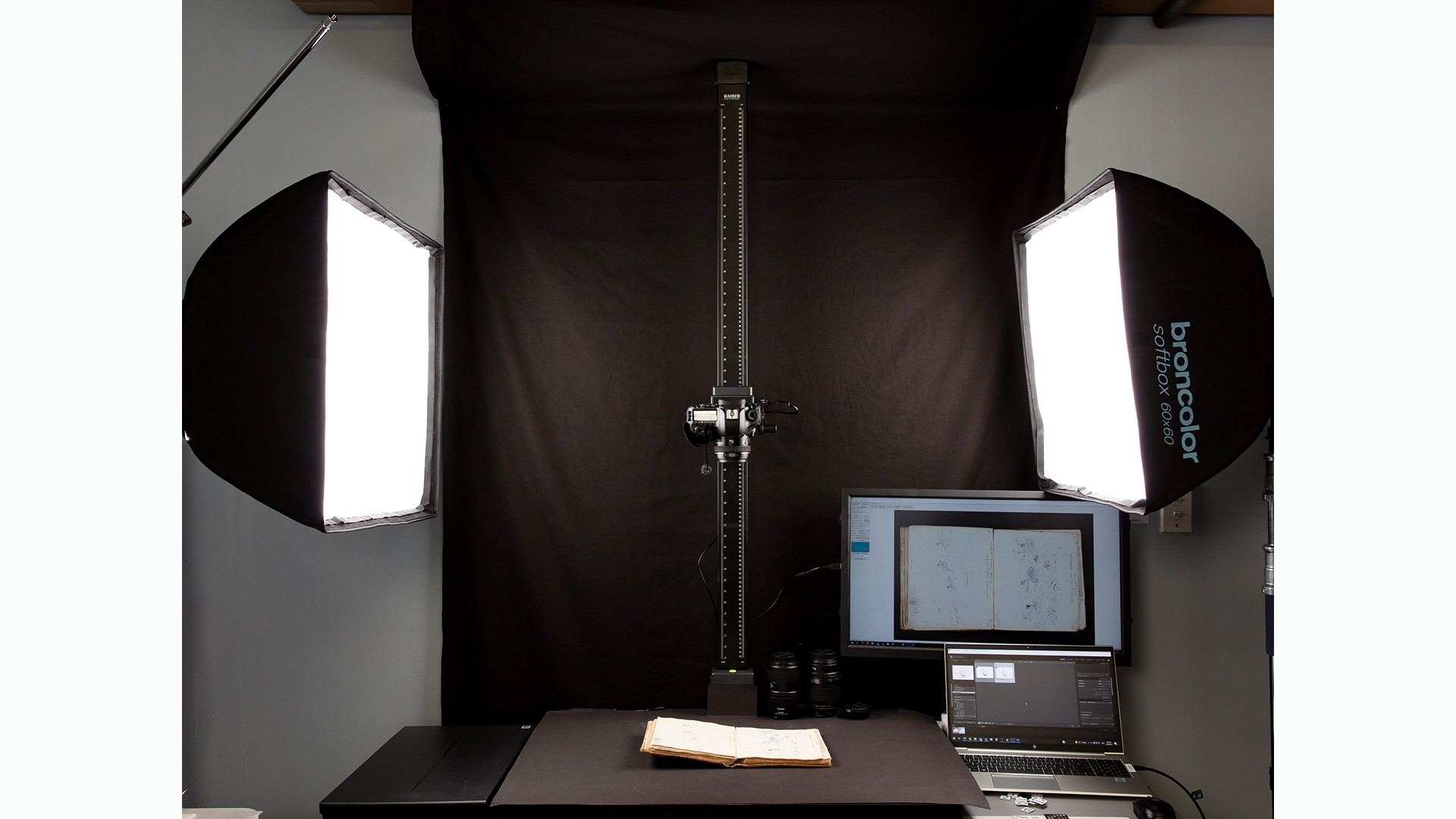

We use Adobe Lightroom Classic to process all our images. Photographs are either processed at the time of import with a pre-set or in the development tab. As we shoot in RAW, all the images are sharpened, because RAW files require this. We ‘enable profile corrections’, which corrects the barrel distortion created by the lens of the camera. The white balance is set to match the colour temperature of the lights and any colour cast from light bouncing off walls etc. The images are then tagged with a selection of keywords: Photographed by/Digitised by, Maritime History, and New Zealand Maritime Museum.

File names are written at point of capture for both scanning and photography. The file names are the museum registration number associated with the object, which links back to the collection database record. If need be, the files can be renamed, singularly or in bulk, through the library tab in Lightroom. Sometimes our sequential numbers may need re-ordering which is when bulk renaming comes in handy!

Once post-processing is finished, all our files are exported from Lightroom. The file formats exported can vary depending on the object photographed. We mainly export an original file for the digital archive, a JPEG image for linking to the database record and Collections Online, and a TIFF file, either 8-bit or 16-bit. A DNG file or a reduced TIFF file can also be exported, again, depending on the objects imaged.

Our general export settings and file specifications are as follows:

Original for archive

- File settings: Image format original

- No settings changed upon export

- Exports the CR2 RAW file if photographed and TIFF file if scanned

- Used for all object/Archive types

JPEG for Vernon (CMS), in-house, researchers

- File export JPEG

- sRGB colour space

- 3000 pixels along longest side, ‘don’t enlarge’ box is ticked

- Output sharpening: sharpen for screen, amount: low

- Exports one JPEG file

- Used for all object/Archive types

Adobe DNG

- File export DNG

- Medium JPEG preview

- Compatibility with Camera Raw

- Embed fast load data

- Used for artworks and objects that have been photographed

8-bit TIFF

- File export 8-bit TIFF

- No file compression

- sRGB colour space

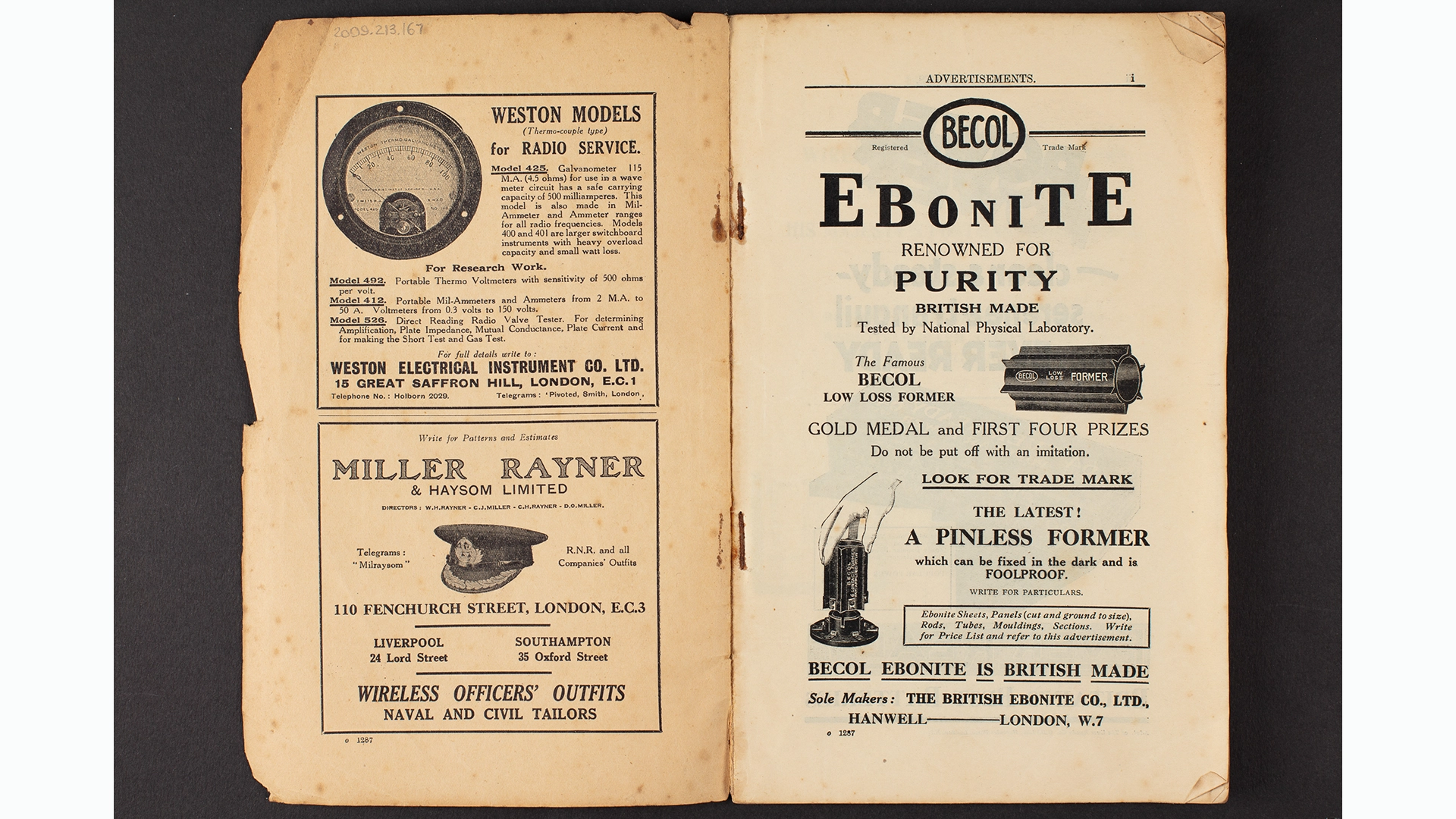

- Used for paper-based archives

16-bit TIFF

- File export 16-bit TIFF

- No file compression

- Adobe RGB colour space

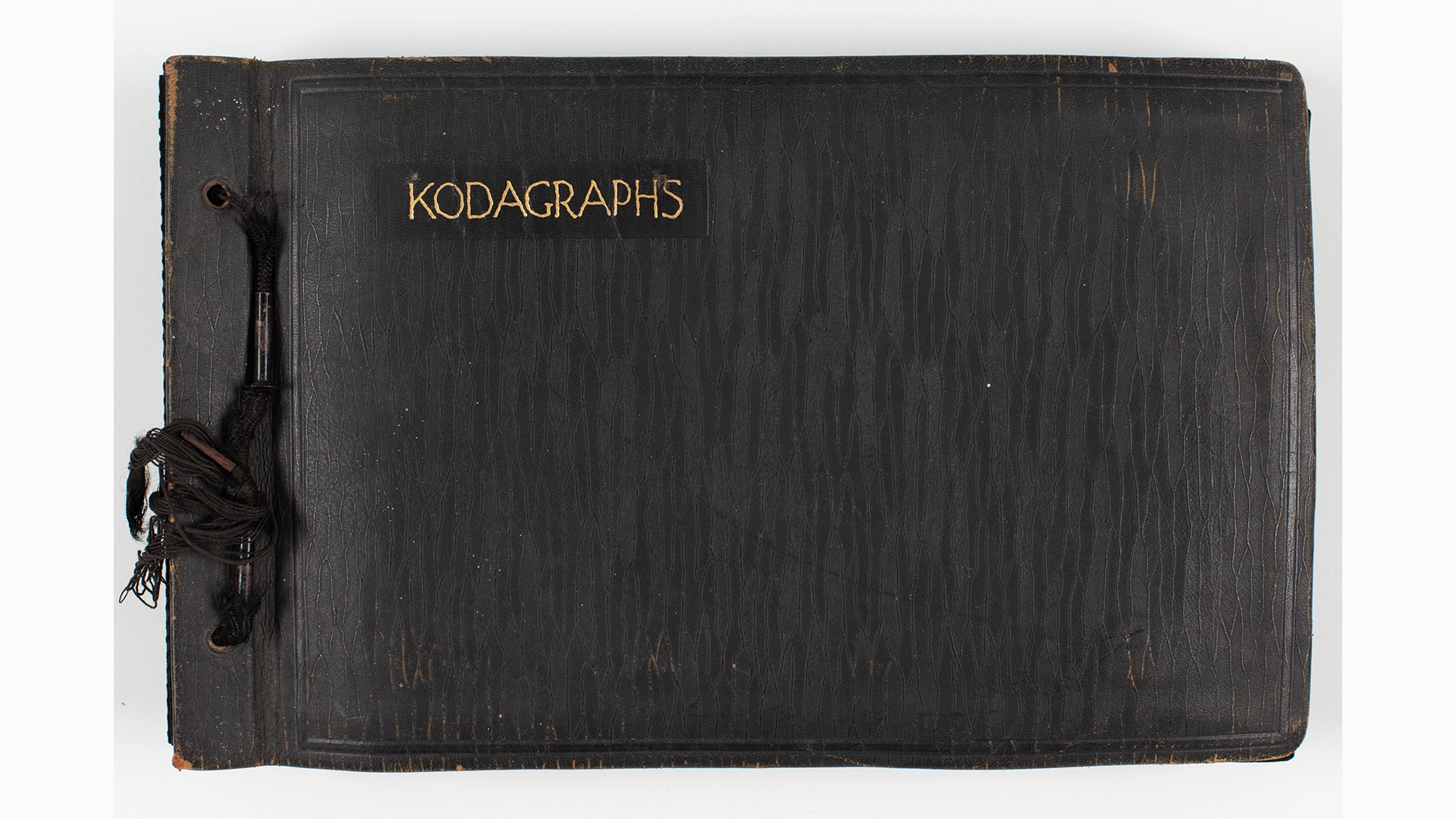

- Used for objects (artworks, albums, medals, etc.)

Reduced Quality 8-bit TIFF, High volume

- File export 8-bit Tiff

- No file compression

- sRGB colour space

- 5000 pixels along longest side, ‘don’t enlarge’ box is ticked

- Output sharpening: sharpen for screen, amount: standard

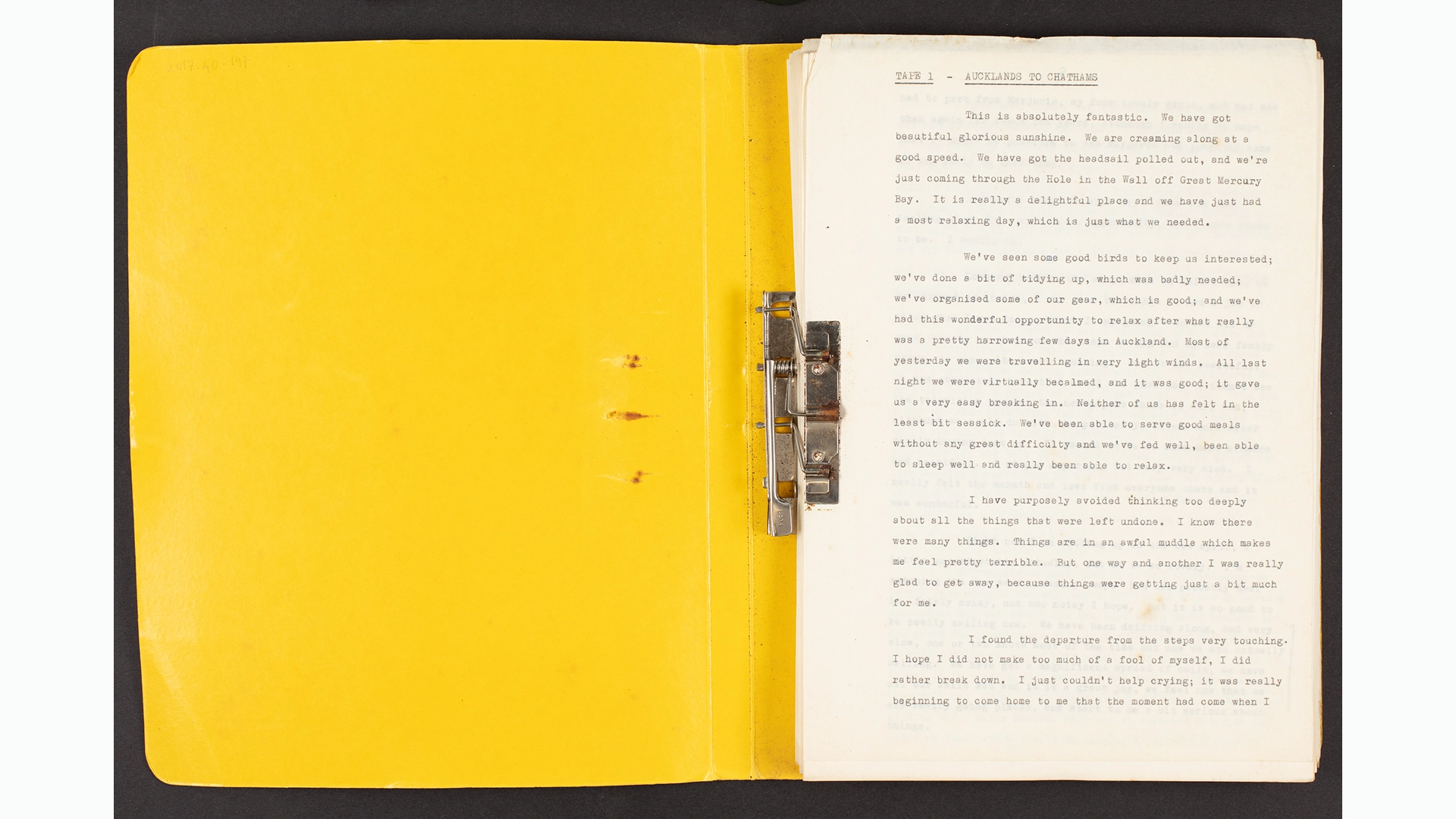

- Used for 100+ page manuscripts, records, logbooks etc. High volume where whats written on the paper is what’s important and the media/paper/material has less value.

Reduced Quality 8-bit TIFF, Lower quality suitable for reproduction at paper’s original size or smaller (aprox A4 and Foolscap),

- File export 8-bit Tiff

- No file compression

- sRGB colour space

- 3600 pixels along longest side, ‘don’t enlarge’ box is ticked

- Output sharpening: sharpen for screen, amount: standard

- Used for Auckland Harbour Board Records, tens of thousands of pages of paper saved at a lower file size to take up as little digital storage space as possible whilst still being a readable surrogate.

Reduced Quality 8-bit TIFF, Lower quality suitable for reproduction at index card size or smaller

- File export 8-bit Tiff

- No file compression

- sRGB colour space

- 2000 pixels along longest side, ‘don’t enlarge’ box is ticked

- Output sharpening: sharpen for screen, amount: standard

- Used for Bill Laxon shipping index cards, these cards are small but numerous, reduced file size for storage purposes whilst still being a readable surrogate.

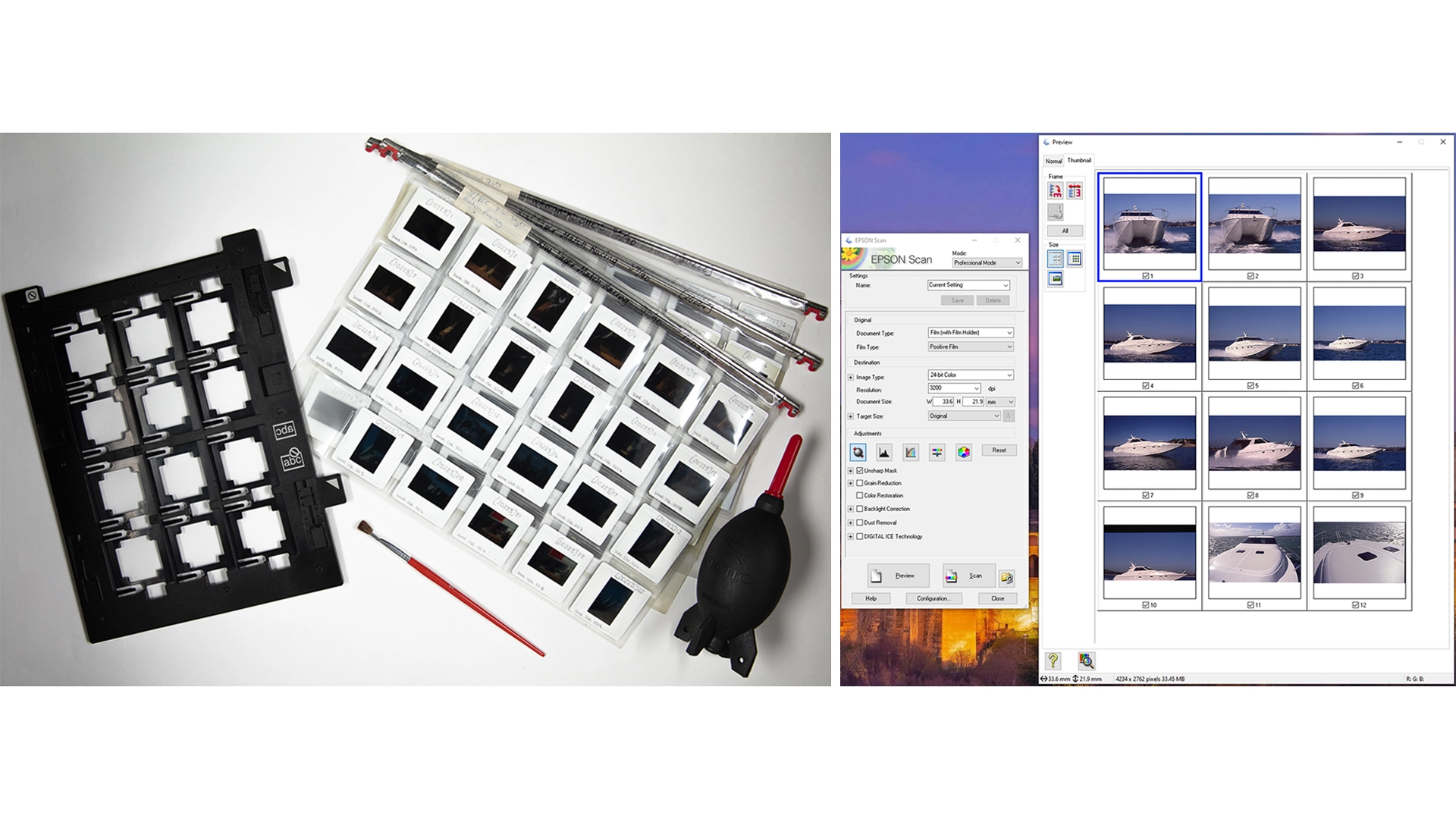

Scanned prints and slides on V800/V850 Epson scanner

- 24-bit Colour setting

- Prints – 1200dpi

- Slides – 3200dpi

- Scan output is an 8-bit TIFF - Original file and JPEG exported from lightroom

As different objects, archives, and size/space issues occur these specifications are tailored as required.

I hope that you, as the reader, have enjoyed this small insight into our 2D copy stand and scanning workflow.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the team I work with for their constant support and teachings, I would especially like to thank Andrew for passing on his knowledge and technical expertise, and I would like to thank the wider Collections Team for being open to teaching and learning new things.